Carissimi amici e

lettori,

Oggi ritorno con

una recensione letteraria. Il libro di cui vi parlo oggi è Preghiera per

Cernobyl della scrittrice Svetlana Aleksievic, giornalista e scrittrice di

origini bielorusse e ucraine, vincitrice del premio Nobel per la letteratura.

Questo libro non esamina gli eventi che hanno condotto all’incidente nucleare

avvenuto nel aprile del 1986 alla centrale nucleare di Cernobyl nell’allora

Unione Sovietica e attuale Ucraina ma raccoglie le testimonianze dei

sopravvissuti, delle persone che hanno vissuto nelle zone contaminate, dei

liquidatori che hanno dovuto limitare i danni delle radiazioni e dei loro figli,

degli scienziati che hanno cercato di limitare i danni, dei soldati chiamati a

sorvegliare la chiusura di villaggi e il trasferimento dei cittadini, dei

contadini che hanno ripopolato i villaggi precedentemente liberati, delle

famiglie povere o in fuga dalla guerra che trovano pace e libertà in una terra

abbandonata, di dottori e personale medico che hanno curato le più diverse

conseguenze patologiche dell’incidente, insegnanti, direttori di musei e

istituti per l’energia nucleare, giornalisti e fotografi che hanno dovuto

coprire l’evento e persino un comunista dichiarato che accusava stati esteri e

i loro servizi segreti per l’incidente senza dichiarare apertamente il suo

nome. Le interviste sono state raccolte a circa 10 anni dal disastro mentre il

libro è stato pubblicato per la prima volta nel 1997 a Minsk. In Italia il

libro è stato tradotto da Sergio Rapetti e pubblicato per la prima volta nel 2002.

Il libro ha ispirato la serie televisiva Cernobyl con Jared Harris e Stellan

Skarsgard.

Svetlana

Aleksievic riproduce fedelmente non solo i fatti narrati da queste persone, ma

anche l’intensità del loro dolore, i colori della loro sofferenza, l’immensità

della loro desolazione, il tormento dei loro rimpianti e delle loro domande.

Alle voci di persone disperate che hanno scelto le terre di Cernobyl per

scapare dalla guerra o dalla povertà e tentare di costruirsi una vita, si

alternano le voci di scienziati che descrivono la fine che hanno fatto coloro

che hanno dovuto intervenire per risolvere e limitare i danni dell’incidente in

quanto quest’ultimi erano deceduti ormai da anni, di liquidatori invalidi o in

fin di vita, ai tempi chiamati ad intervenire per ridurre il danno all’ambiente

ed al pianeta, di loro parenti sopravvissuti, di professori e dottori che

curano i loro figli. Mentre il rifiuto cociuto dei contadini di abbandonare la

loro terra e dei nuovi immigrati di non insediarsi sulle terre evacuate,

potrebbe far arrabbiare, infine risulta comprensibile viste le loro conoscenze

di fisica. Per loro è inconcepibile come una cosa invisibile all’occhio nudo

possa danneggiare la loro salute e addirittura ucciderli. Le voci dell’altra categoria

di persone non lamentano il rifiuto ma bensì l’impossibilità di poter

beneficiare di un tale privilegio e la mancanza d’informazioni che gli

avrebbero condotti alla cautela. Il cordone centrale delle loro testimonianze

riguarda la mancanza di comunicazioni, la manipolazione e quando esse non

funzionavano, le intimidazioni, usate per far si che loro restassero e

contribuissero a salvare il mondo. Ad impressionare e orripilare il lettore

invece è l’indifferenza criminale con la quale queste persone erano inviate a

svolgere il loro lavoro senza equipaggiamento adatto, mascherine di protezione,

dosimetri funzionanti, terapie di prevenzione con iodio o accurata

informazione. Lo scopo di tutto ciò era avere dei lavoratori che svolgessero

questi lavori cruciali per l’umanità ma anche costruire e diffondere una

propaganda che sminuisse la gravità del disastro e dipingesse l’immagine di un

paese all’avanguardia capace di risolvere qualsiasi problema. Mentre il popolo

veniva nutrito addirittura con il raccolto proveniente dalle terre vicine al

reattore e con il latte e la carne degli animali che venivano eliminati, per

via dell’ignoranza dei contadini che vendevano i prodotti ad estranei e delle

macchinazioni delle categorie dirigenti, i “capi” che prendevano le pastiglie

di iodio, avevano equipaggiamenti adatti e consumavano pasti provenienti da

zone non contaminate. La distinzione fra le persone comuni che vedevano

calpestare i loro diritti esistenziali e le figure del partito, sono notevoli e

diventano più struggenti con ogni testimonianza. Alcune frasi pronunciate dai

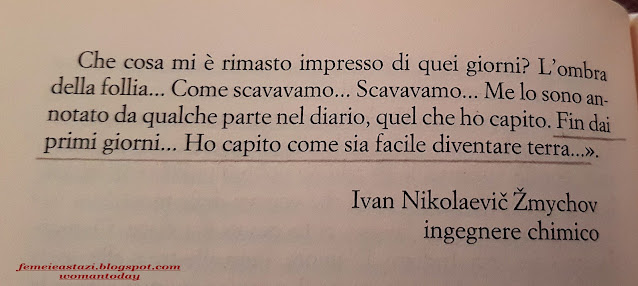

liquidatori intervistati rimarranno nella mia mente per sempre: “Ci hanno

gettati laggiù come sabbia sul reattore”, “Quando sono rientrato

dall’Afghanistan, lo sapevo per certo: ce l’ho fatta a tornare, dunque vivrò!

Ma con Cernobyl è tutto il contrario: ti ammazza dopo che sei tornato…” (p.94)

o “chiamava […] gli uomini «terra che parla»”(p.117). La situazione

privilegiata dei dirigenti di partito viene descritta accuratamente dagli

scienziati che hanno faticato inutilmente per convincerli ad adottare misure

corrette per tutti. La conclusione dei loro racconti è la stessa in ogni caso:

“per quelli che stanno in alto la gente è l’ultimo pensiero, temono solo per il

proprio potere” (p.251), “i nostri dirigenti avevano più paura della collera

dei propri superiori che dell’atomo” (p.252). Essere al di sopra del popolo

crea la sensazione di potere: “smisurato potere di un uomo su un altro. Non è

più solo un inganno, è una vera e propria guerra, una guerra contro gli

innocenti…”(p.254) cosi tutto questo diventa storia, “la storia di un crimine”

(p.253). E la storia viene costruita a piacimento grazie alla propaganda, una

propaganda attentamente sorvegliata dal KGB che vieta di filmare o fotografare

gli eventi in corso, sviando l’attenzione del mondo con scene costruite a

tavolino come l’agricoltore sul trattore che legge un giornale di carattere

comunista o il matrimonio organizzato sulla terra del Cernobyl per una coppia

evacuata da tempo ma fatta tornare appositamente per questo. La scrittrice

sceglie di far presente sin dall’inizio lo scopo della propaganda attraverso le

parole di un giornalista: “Non dimentichi che abbiamo dei nemici. Abbiamo molti

nemici al di là dell’oceano […] ecco perché da noi tutto va sempre bene, e non

c’è niente che vada male.”

Il romanzo inizia e finisce con i racconti dolorosi di

due mogli di vittime di Cernobyl. La prima, è la moglie del pompiere chiamato a

spegnere quello che inizialmente sembrava un incendio alla centrale e se avete

visto la serie televisiva, il film è stato abbastanza preciso. Non ha colto e

trasmesso tutti i dettagli di un evento talmente tragico ma non vorrei rovinare

la sorpresa di scoprirli personalmente nel caso vogliate leggere anche il

romanzo quindi non aggiungo niente a questo punto. La seconda testimonianza

invece, che ha ispirato anche il titolo del libro, almeno nella traduzione in

italiano, è la testimonianza della moglie di un liquidatore, un uomo sposato

con figli. Al momento della selezione per andare a Cernobyl e anche al ritorno,

non erano al corrente dei rischi ai quali sarebbero stati esposti. Al ritorno,

egli non raccontò molto di quello che aveva visto o sentito e quindi il

calvario inizio con i compagni che iniziarono ad ammalarsi e morire entro i 3-4

anni da quando fossero rientrati a casa. Questa testimonianza è una prova di

dedizione e amore incondizionato verso un marito moribondo e un figlio malato.

Credo che con queste due storie l’autrice del romanzo ha voluto dare voce anche

alla popolazione femminile apparentemente ignorata in questo disastro. Le

donne, a meno che non si offrissero volontarie, non furono coinvolte nelle

attività di liquidazione dell’incidente. Le loro figure vengono menzionate fra

le testimonianze del personale medico, scientifico, didattico oppure

semplicemente come le persone che hanno assistito gli uomini con attività di

pulizie e quindi senza un’esposizione diretta alle radiazioni perciò il modo in

cui questo disastro aveva toccato le loro vite, era incompleto. Essi hanno

assistito gli uomini nella malattia, nel dolore e nella sofferenza facendo in

modo che la morte sembrasse meno crudele e violenta. Essi hanno sofferto

insieme ai loro uomini, sono morte interiormente insieme a loro e bisognava

raccontare questo travaglio. Le loro voci dovevano essere ascoltate per

comprendere a pieno la dimensione della sofferenza che un simile evento può

causare.

Per concludere, io vorrei lasciarvi con le parole di un

coro di bambini, bambini che nella loro innocenza accettano saggiamente la

morte nonostante non capiscano perché devono morire…

“Moriremo e diventeremo scienza” diceva Andrej.

“Moriremo e ci dimenticheranno” pensava Katja.

“Quando morirò, non seppellitemi al cimitero, il cimitero

mi fa paura, ci sono soltanto morti e cornacchie. “Seppellitemi nei campi…”

aveva chiesto Oksana.

“Moriremo” piangeva Julja. Per me adesso il cielo è vivo…

Quando lo guardo… loro sono là…» (p.272)

ENGLISH

Dear friends and readers,

Today I return

with a literary review. The book I am talking about today is Prayer for

Chernobyl by writer Svetlana Aleksievic, a journalist and writer of Belarusian

and Ukrainian origins, winner of the Nobel Prize for literature. This book does

not examine the events that led to the nuclear accident that took place in

April 1986 at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the then Soviet Union and

present day Ukraine but collects the testimonies of the survivors, of the

people who lived in the contaminated areas, of the liquidators who had to limit

the damage of radiation and their children, scientists who tried to limit the

damage, soldiers called to oversee the closure of villages and the transfer of

citizens, peasants who repopulated previously liberated villages, poor families

or refugees of war who seeked peace and freedom in an abandoned land, of

doctors and medical personnel who have treated the most diverse pathological

consequences of the accident, teachers, directors of museums and institutes for

nuclear energy, journalists and photographers who have had to cover the event

and even an outspoken communist man blaming foreign states and their secret

services for the accident without openly stating his name. The interviews were

collected about 10 years after the disaster while the book was first published

in 1997 in Minsk. In Italy the book was translated by Sergio Rapetti and

published for the first time in 2002. The book inspired the television series

Chernobyl with Jared Harris and Stellan Skarsgard.

Svetlana

Aleksievic faithfully reproduces not only the facts narrated by these people,

but also the intensity of their pain, the colors of their suffering, the

immensity of their desolation, the torment of their regrets and their

questions. To the voices of desperate people who have chosen the lands of

Chernobyl to escape from war or poverty in order to build a life are alternated

the voices of scientists describing the fate of those who had to intervene to

solve and limit the damage of the accident as the latter had died years before,

of invalid or dying liquidators, at the time called to intervene to reduce the

damage to the environment and the planet, to their surviving relatives, to

professors and doctors who were treating their children. While the stubborn

refusal of peasants to abandon their land and of new immigrants not to settle

on the evacuated lands may anger the reader, finally it is understandable given

their little knowledge of physics. For them it is inconceivable how something

invisible to the naked eye can damage their health and even kill them. The

voices of the other category of people do not complain about the refusal but

rather the impossibility of being able to benefit from such a privilege and the

lack of information that would have led them to be cautious. The central cord

of their testimonies concerns the lack of communication, the manipulation and

when all this did not work, the intimidation, used to make them stay and help

save the world. What impresses and horrifies the reader, on the other hand, is

the criminal indifference with which these people were sent to carry out their

work without suitable equipment, protective masks, working dosimeters,

preventive therapies with iodine or accurate information. The purpose of all

this was to have workers who carry out these crucial jobs for humanity but also

to build and disseminate propaganda that diminished the severity of the

disaster and painted the image of a magnificent country, capable of solving any

problem. While the people were actually fed the harvest coming from the lands

near the reactor and the milk and meat of the animals that were eliminated, due

to the ignorance of the farmers who sold the products to strangers and the

machinations of the ruling categories, the " leaders ”who took the iodine

tablets, had suitable equipment and ate meals from uncontaminated areas. The

distinction between ordinary people who saw their existential rights trampled

on and party figures, is remarkable and becomes more obvious with each

testimony. Some phrases spoken by the liquidators interviewed will remain in my

mind forever: "They threw us down there like sand on the reactor",

"When I returned from Afghanistan, I knew for sure: I made it back, so

I'll live! But with Chernobyl it is quite the opposite: he kills you after you

come back ... "(p.94) or" he called [...] people "speaking

land" (p.117). The privileged situation of party leaders is accurately

described by scientists who have worked in vain to persuade them to take

measures that are correct for all. The conclusion of their stories is the same in any case: "for those who stand above, people are the last thought, they fear only for their own power" (p.251), "our leaders were more afraid of the anger of the one's superiors than of the atom ”(p.252). Being above the people creates the feeling of power: “one man's immeasurable power over another. It is no longer just a deception, it is a real war, a war against the innocent… ”(p.254) so all this becomes history,“ the story of a crime ”(p.253). And the story is built at will thanks to propaganda, a propaganda closely guarded by the KGB that prohibits filming or photographing the events in progress, diverting the attention of the world with scenes built at the table like the farmer on the tractor reading a newspaper. Communist character or the wedding organized on the land of Chernobyl for a couple evacuated for some time but returned specifically for this. The writer chooses to point out the purpose of propaganda from the beginning through the words of a journalist: "Don't forget that we have enemies. We have many enemies across the ocean [...] that's why everything is always good with us, and nothing could go wrong. "

The novel begins and ends with the painful tales of two wives of Chernobyl victims. The first is the wife of the firefighter called to put out what initially looked like a fire at the plant and if you have seen the television series, the film was quite accurate. He has not grasped and transmitted all the details of such a tragic event but I would not want to spoil the surprise of discovering them personally in case you want to read the novel too so I will not add anything at this point. The second testimony, on the other hand, which also inspired the title of the book, at least in the Italian translation, is the testimony of the wife of a liquidator, a married man with children. At the time of the selection to go to Chernobyl and also to return, they were not aware of the risks to which they would be exposed. Upon returning, he did not tell much about what he had seen or heard and therefore the ordeal began with the companions who began to get sick and die within 3-4 years of returning home.

This testimony is proof of dedication and unconditional love for a dying husband and a sick child. I believe that with these two stories the author of the novel also wanted to give a voice to the apparently ignored female population in this disaster. The women, unless they volunteered, were not involved in the settlement of the accident. Their figures are mentioned among the testimonies of medical, scientific, educational staff or simply as the people who assisted men with cleaning activities and therefore without direct exposure to radiation therefore the way in which this disaster had affected their lives, it was incomplete. They assisted men in sickness, pain and suffering by making death seem less cruel and violent. They suffered together with their men, they died inwardly with them and it was necessary to tell about this travail. Their voices had to be heard to fully understand the dimension of suffering that such an event can cause.

To conclude, I would like to leave you with the words of a choir of children, children who in their innocence wisely accept death despite not understanding why they had to die ...

“We will die and become science” said Andrei.

“We will die and they will forget us” Katja thought.

“When I die, don't bury me in the cemetery, the cemetery scares me, there are only dead and crows. "Bury me in the fields ..." Oksana asked.

“We will die” Julja cried. For me now the sky is alive ... When I look at it ... they are there ... "(p.272)

IT: Per realizzare questa recensione secondo la regolamentazione del fair use, ho letto il libro Preghiera per Cernobyl di Svetlana Aleksievic, editore E/O, collana Le cicogne, 2018, EAN 9788866329572

EN: To carry out this review according to the fair use regulation, I read in Italian the book Prayer for Chernobyl by Svetlana Aleksievic, publisher E / O, Le cicogne series, 2018, EAN 9788866329572

Disclaimer

e premesse / Disclaimer and premises

IT:Questo post non ha scopi commerciali e non incoraggia

vendite, denominazioni, immagini ed eventuali link presenti sono solo a scopo

informativo. Le immagini ritraggono un prodotto acquistato regolarmente che ho

valutato in quanto consumatore. Questo post è di mia completa creazione per

quanto riguarda contenuti, foto e idee espresse. Prima di usare qualsiasi parte

di questo post siete pregati di contattarmi e nel caso vi abbia ispirato per

altre creazioni, vi chiedo cortesemente di menzionare la fonte.

ENG: This post

has no commercial purposes and does not encourage sales, names, pictures and

eventual links are present only for an informative purpose. The opinions

expressed represent my experience as a consumer. This post is of my entire

creation as for contents, photos and expressed ideas. Before using any part of

it, you need to contact me and in case it inspired you for other creations, I

gently ask you to mention the source.